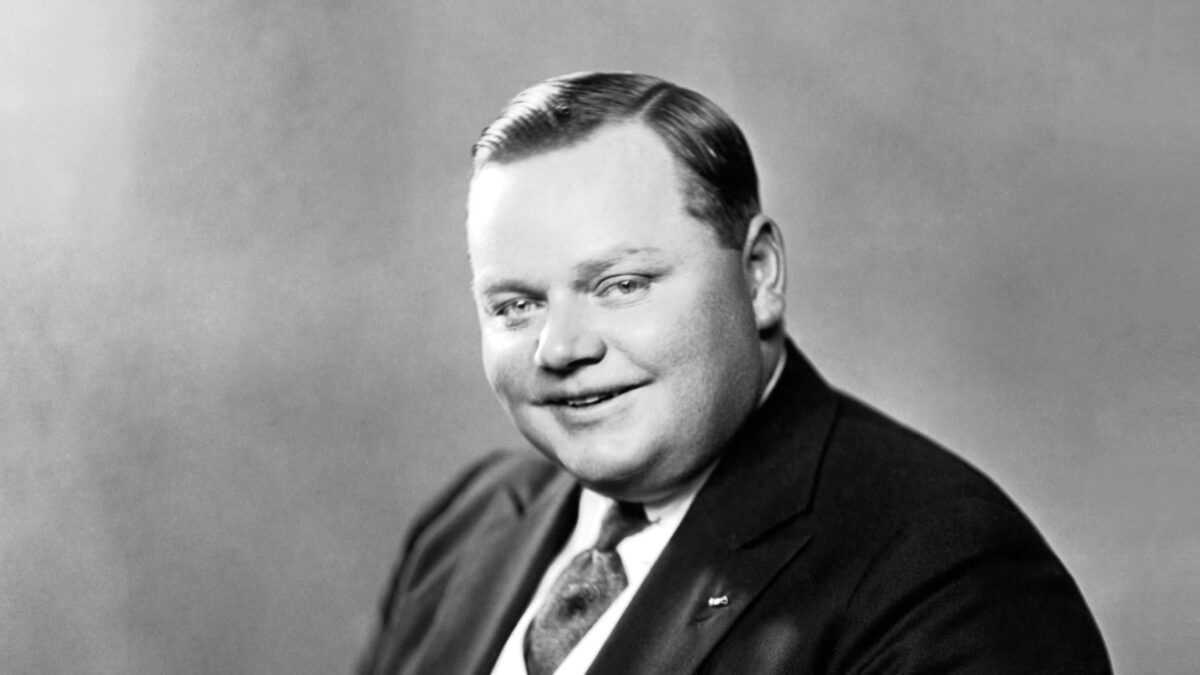

Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle: Silent Film’s Fallen Star

In the early days of Hollywood, before the rise of the modern movie star system, few actors were as famous as Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, a gifted entertainer whose name is more synonymous with Hollywood scandal than any of his performances. At the height of his career, he was one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood. However, a scandal in 1921 changed his legacy forever.

Early Life

Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle was born on March 24, 1887, in Smith Center, Kansas, the youngest of nine children to parents Mary Gordon Arbuckle and William Goodrich Arbuckle. His birth was difficult, especially for his mother, as he weighed over 13 pounds at birth. His father, a harsh and often cruel man, gave his son the name after Roscoe Conkling, a politician he despised, as a form of mockery. Additionally, William thought Roscoe might be the result of an affair as both William and Mary were small thin people.

When Arbuckle was a year old, the family moved to Santa Ana, California. At a young age, he showed a natural talent for singing and performing. He first sang onstage when he was just eight years old. But his weight made him the target of ridicule and physical abuse from his father. His mother, who was supportive and loving, encouraged his creativity, but she passed away when he was only 12. After his mother’s death, William abandoned Roscoe.

Forced to support himself at a young age, Roscoe took jobs in hotels and theaters, eventually finding work as a singer and performer in vaudeville. His natural agility, despite his size, made him a standout on stage. One story—possibly exaggerated—claims that a theater manager pushed him onto the stage during an amateur contest, and Arbuckle won over the audience with a spontaneous comedic performance. Whether true or not, his talent was undeniable, and it wasn’t long before he was working steadily in show business.

Career

Arbuckle worked with various theaters and performing groups traveling all over the world. His film career began in 1909 when he joined Keystone Studios, appearing in his first film, Ben’s Kid. He became known for his physical humor, which relied not just on pratfalls but on his remarkable agility and expressive face. Unlike other large comedians, Arbuckle never played the clumsy oaf. Instead, his characters were often graceful, charming, and clever.

He was not a fan of the name “Fatty.” However, he went along with it, knowing that it helped his career. He made it clear to people not to refer to him as Fatty off-screen.

By the mid-1910s, Arbuckle had become one of Hollywood’s biggest stars, figuratively and literally, weighing around 250 to 300 pounds. He frequently collaborated with other comedy legends, including Mabel Normand and Buster Keaton. In 1914, Paramount Pictures offered him $1,000 a day plus 25 percent of each film’s royalties and creative control over his movies, an impressive offer at the time. A few years later, he partnered with Joseph M. Schenck to form his own production company, Comique Film Corporation, where he had full creative control over his films.

Arbuckle’s popularity continued to soar, and in 1920, he signed an unprecedented contract with Paramount Pictures for $3 million over three years. His films, such as The Round-Up (1920) and Brewster’s Millions (1921), were major box office successes, making him one of the most beloved figures in Hollywood.

Scandal and Trial

Along with some friends, Arbuckle rented three rooms to throw a Labor Day party in September 1921 at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco. Despite Prohibition, alcohol was widely served and enjoyed among many of the party guests, including a young actress named Virginia Rappe. At the party, Rappe fell seriously ill, with most people believing that she was highly intoxicated. She was seen by the hotel doctor, who also believed she was intoxicated and gave her some morphine. Not getting any better, Rappe was eventually taken to the hospital, where she died a few days later due to peritonitis resulting from a ruptured bladder – something that is very rare. Rappe had existing bladder issues, and it is now believed that drinking alcohol contributed to her existing issues.

Witnesses, including Rappe’s companion Bambina Maude Delmont, claimed Arbuckle had been alone with her in a hotel room and accused him of sexually assaulting her. Even though an autopsy concluded that there were no signs of violence on her body, and when she was being treated in the hospital, Rappe had never mentioned being assaulted to doctors before she died.

Arbuckle was charged with manslaughter, which was contested in three highly publicized trials. Authorities accused him of forcing himself on Rappe, and his weight contributed to her bladder rupturing and death. Arbuckle said that he found Rappe in pain and vomiting in a bathroom and that he carried her to a bed and then got her help.

The trial became one of the first major Hollywood scandals, and the public turned against him almost immediately due to the sexualized nature of the situation. Newspapers, such as those owned by William Randolph Hearst, used the scandal to increase sales as an example of Hollywood’s debauchery with celebrities drinking, doing drugs, and having orgies. It didn’t help Rappe’s reputation either, as she was referred to as a promiscuous drunk.

The first two trials ended in hung juries, but in the third trial, where the jurors only took six minutes to deliberate, Arbuckle was acquitted. The jury even issued a formal apology, stating that “a great injustice has been done to him… there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime… Roscoe Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame.” Maude Delmont was eventually found to be lying and using the situation to extort money from Arbuckle. The prosecutor in the case was caught encouraging witnesses to make false statements to further his career.

Even though friends such as Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and his wife Minta Durfee spoke out in his defense and his legal victory, his reputation was destroyed. Hollywood studios, fearing a backlash, banned his films and cut ties with him. His career came to an abrupt end.

Aftermath

Because alcohol was consumed at the party, Arbuckle pled guilty to one count of violating the Volstead Act and paid a $500 fine (approx. $9,000 in 2025). He owed more than $700,000 (approx. $13 million in 2025) in legal fees. He was forced to sell his house and cars to pay some of the debt.

After the scandal, Arbuckle struggled to find work. Just like today, the accusation is often enough to destroy a career. Will H. Hays, head of the newly formed Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America, issued a temporary ban that would prohibit Arbuckle from working in film and that any showings of Arbuckle’s films be canceled. Paramount withdrew his completed films, Crazy to Marry, Leap Year, and The Fast Freight.

Arbuckle was eventually able to find some work directing using his father’s name as a pseudonym, William Goodrich, but his days as a leading man were over. He spent years in relative obscurity, occasionally acting in small, uncredited roles. His friend Buster Keaton provided him assistance by hiring him to work as a writer and director for some of his films and provided him with a percentage of the profits of Buster Keaton Comedies.

Personal Life and Legacy

Arbuckle was married three times, the first to actress Minta Durfee in 1908. The two separated in 1921, just before the scandal, and divorced in 1925. Although divorced, she often spoke positively about Arbuckle. He married Doris Deane in 1925, and the two divorced in 1928. His final marriage to Addie McPhail was in 1932.

Eventually, there were signs of a comeback. Arbuckle appeared in a series of comedy shorts under his own name, and he signed a contract to star in a feature film for Warner Bros. On June 28, 1933. He celebrated his new contract with friends, telling them, “This is the best day of my life.” That night, he suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 46.

For decades, Arbuckle’s name was synonymous with scandal, overshadowing his contributions to early film comedy. Like many films from that era, much of his work has been lost to time. Additionally, due to the scandal, some studios deliberately destroyed prints of his films. However, not all were lost, and some of his silent films have been rediscovered and remain available to audiences today. Still, his legacy will always be tied to that night in September 1921.

Tags In

Related Posts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.